There are plenty of photo articles about Mongolia’s summer beauty, but none that show the wild winter landscape, and the country is only just beginning to open its doors to adventurers. Sophia Roberts and I have traveled to this previously uncharted, icy land as guests of Nomadic Expeditions.

Like Saint Tropez, Ulaanbaatar has a short tourist season in July and August, when flights are hectic and it can be difficult to get a reservation at the city’s best hotels. Mongolia, with its capital, Ulaanbaatar, is roughly the size of Western Europe. On Sunday mornings, Mongolians gather in their families at the brand-new Shangri-La Hotel to feast on dumplings and sip imported wine with foreign guests who have come to watch this year’s summer festival. (Mongolia has had one of the highest GDP growth rates in the world for the past five years.)

It is the country’s biggest and most popular festival, held in July, and around 5,000 people gather on the outskirts of Ulaanbaatar, or “UB,” to watch archers, wrestlers and children racing their horses. Hotels with few beds to meet the demand of the tourist season are struggling in July. The Naadam coincides with the arrival of 53 heads of state and government for the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) this week. Alice Daunt, a luxury travel company based in London, has resorted to Airbnb to help accommodate more than 100 of its clients.

“This short tourism cycle is really putting us in a difficult position,” said Jalsan Urubshurov, founder of Nomadic Expeditions, a major tour operator in the country that has organized Buddhists such as Richard Gere and Robert Thurman to travel to Mongolia for the past 25 years. “Summer is beautiful, but this country is not just a festival under the sun, there are many other beautiful places to visit. Just a short drive from Ulaanbaatar, you will reach some of the least densely populated wilderness areas on earth. Spring and autumn are a lost opportunity. In winter, the number of tourists is even less, almost zero,” he said. “If you go to the remote regions, you will feel how magical Mongolia is. The first snow is the best time of the year for me,” he added.

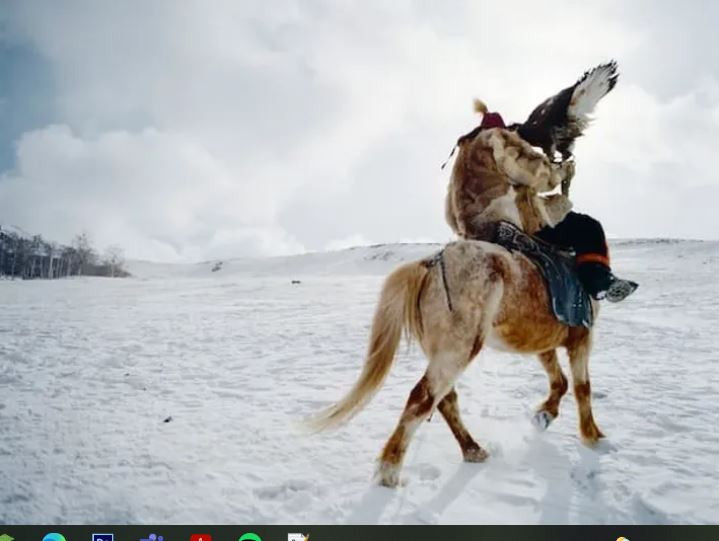

Urubshurov has spent the past 10 to 15 years of his life, and even his own money, developing the festival, which is held in the first week of October every year, to revive the traditions of Kazakh nomadic eagle hunters living in Bayan Ulgii province, at the foot of the Altai Mountains. Today, in the pristine wilderness of Altai, which even Mongolians consider the edge of the world, more than 300 tourists a year come through the Nomadic Expeditions company during the “non-tourist” season, staying in Urubshurov’s $1,000-a-day ger camps, eager to watch the horsemen in sable-colored robes and golden eagles with their 7-foot wingspans compete.

Encouraged by the success of his eagle festival, Urubshurov’s company now brings tourists even in the dead of winter, and recently began hosting a large number of tourists who had come to rely on simple comforts at the Ice Festival, which was held on the ice of Lake Khuvsgul in the Sayan Mountains in the northwest of the country.

PREPARATIONS FOR THE ICE FESTIVAL ON KHUVSGUL LAKE

When I came to Mongolia to witness this event, it was the cold, thin snow days of March, when, as the nomads say, “the tail of an ox freezes,” as Urubshurov said, it turned out to be true. This is a truly beautiful place, with snow mist and swirling wind, and the land, as if wearing a white robe, is a reflection of the purity of nature. The snow on roads, rivers, and streams, like the snow on the bare grass, disappears under the feet of grazing animals, and then the frozen lake is covered with snow like an ocean. Although I did not fly in the luxuriously equipped new MI-8 helicopter that Urubshurov rents to his high-profile clients, I traveled with full of adventure due to the time and the terrain, and I did not get cold and comfortable. We had lunch at a new camp with a ger located right in the middle of the lake, and stayed overnight at two comfortable lodges: “Ashihai” on the south side of the lake and “Hirves Inn” (Last Frontier camp) on the north side.

Built on the banks of the Khovd River, our own mobile camp, with a wood fire and camel wool and goat cashmere blankets, will be set up for the Urubshurov Burgedi festival next year, and its chef will be preparing sharvin for breakfast and Mongolian goat stew for dinner.

A YOUNG MAN ON A HORSE WITH A GOLDEN EAGLE AT A NOMAD HUNTING TRADITION

This time, however, I was more worried and afraid of the crevices in the lake ice than of Urubshurov’s cellar, where he keeps the fortified wines he takes with his high-class tourists on his mysterious journeys through the vast expanses of Mongolia. Yes!. Our Land Cruiser glided smoothly over the frozen blue ice like a speedboat, almost dancing on the surface, swaying with the wind. However, when the temperature drops below 30 degrees Celsius, crossing the frozen lake presents some serious risks. According to our guide, Dorj (George), this winter alone, three cars have fallen into the lake ice!

TRAVELING ON THE ICE OF LAKE KHUVSGUL BY CAR

The dark, icy ice beneath our feet added to our sense of awe. Lake Khuvsgul is 267 m deep at its deepest point and is the second-freshest lake in the world after Lake Baikal in Siberia. The two lakes are located on the same geographical level as the Great Rift Valley, a vast continental divide that stretches 2,000 km from northern Mongolia to the Arctic. Earthquakes are common, with some scientists estimating that about 650 m of earthquakes occur annually, making these two lakes unique in the Eurasian continent. The tectonic tremors of the lake ice are unlikely to deter the continuous caravans of Mongolian nomads who travel to the ice festival in all kinds of vehicles.

Some people arrive by 90-minute flight from Ulaanbaatar to the airport in Murun, 90 kilometers from the lake. Some have traveled 10 hours on a new road built with the money that the country’s economy has received from mining, about 680 kilometers from the capital. At the beginning of our journey, we saw herders pulling small horses with leather sleighs decorated with bells and colorful felt, traveling along the lake. Nine members of a family were riding on one sleigh, wrapped in warm blankets that smelled of wood. As they talked, their breaths were so cold that they froze in the air. Traditional ger houses were built on the shores of the lake, and the smoke from their chimneys billowed over the roofs of the houses and weaved its way through the thickets of Siberian larch trees.

On our way, we passed people in green Russian UAZ-452 vans, classic Cold War VWs, who were on their way to the Ice Festival. A few nomads were riding motorcycles, some even in open cars. We also met a wealthy expedition group from Ulaanbaatar, who were riding mountain bikes with spikes like iron teeth to cut through the ice, and who were traveling around the lake at speeds of up to 70 kilometers per day. Some of the more well-to-do men were accompanied by their round, white-faced wives, who wore their national robes, which were a bit silkier and buttoned up at the neck than the Khuvsguls. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, a lot of money has been pouring into the country thanks to gold and copper. Yes, Mongolians, no matter how big their new Toyota 4WDs are, still maintain their nomadic roots.

According to Ms. Naranchimeg, the head of the Khuvsgul Tourism Association, 7,000 people are participating in this festival, and events such as ice skating, skating, wrestling, horse-drawn sleigh races and a competition for the best-dressed couples are held. More than a tourism festival, this event feels like a party where locals and strangers meet. They meet and have fun with relatives and friends. Alcohol is drunk, and every party is called a must. When talking about this festival, it can be said that the bottom of the thermometer freezes into a ball in the winter.

LOCAL CITIZENS TRAVEL ON HORSE-SLEDS ON THE ICE OF THE LAKE

One of the ice sculptures at the Khuvsgul Lake Ice Festival

We traveled 136 km across Khuvsgul Lake to reach the northern tip of the lake while the sky was still clear, and we had to return to the ice festival site the next day. On the way, we stopped at a new ger camp on a small island in the middle of the lake and had a delicious lunch. According to Dorje, moose come to this island in the summer to eat. We drank a lot of vodka, ate spoonfuls of fish caviar, and warmed ourselves by the fire. The large ger at the camp is white with orange accents and seems to have merged with the island’s cedar forest. The snow here is about a meter thick and it falls from the trees like a glove of ice. This camp is called “Lost World” and gives the impression of a Swiss chalet /small house/ set in a snowdrift. I was the first tourist to visit this camp.

Lake Khuvsgul is a place with a very ancient history and a shamanic culture. On our way north of the lake, we came across otogs, tribal pilgrimage poles, and mounds as we headed to the sacred Munkh Sardag peak of Buren Khan Mountain, which rises on its northern shore. Our journey was not always a straight line. Our driver, a famous wrestler in the area, spent an hour and a half trying to cut through the ice like a giant wall to make a comfortable path. This high wall, like an iceberg, was formed by the flow of water and the force of the wind when the lake first froze. It moved like a huge mountain throughout the winter, and by the time we reached Khankha, its position had changed depending on the weather, which had begun to deteriorate. I rested comfortably in this village called Khankha, which has a population of about 2,500. It was very hot, so I got up and opened the window of my room. We entered a traditional Russian banya on the lakeshore and ate grilled hadran fish in a wood-paneled dining room. The weather outside was warming up at this quaintly named place, the Last Frontier, or the Hirves Inn.

The Ashihai Camp on the shores of Lake Khuvsgul

By the time we got back to the ice festival, the weather had deteriorated, and it was the worst storm I’ve ever seen in my life, let alone in Antarctica. Wind speeds reached 57.6 km/h. At one point we were traveling at less than 8 km/h, and we couldn’t see anything more than a meter or two. The head of the government search and rescue department on Lake Khuvsgul said that by 10 p.m., 130 people were missing nationwide, all roads were closed, and 30 people were missing at the ice festival. Their team spent the entire night searching the lake. Fortunately, no one was killed.

The organizers of the Mongolian Ice Festival didn’t let the weather spoil their holiday experience. We visited their homes, shared food and drinks, and felt like we were part of their culture. I only met four other foreigners that day. “It’s a good thing we managed to get the horse race out of this bad weather,” said Dorj, who was chatting with friends on the streets of England on a warm summer day in the middle of the snowstorm. The children, meanwhile, were playing as if they were in a New York summer park. The ice skaters were reluctant to let the weather ruin their work, and no one complained. I didn’t think much of the delay in my flight back to Ulaanbaatar. In fact, I wished the plane had landed a day later.

Leave a Reply